The judges who gave Margaret Renkl the 2022 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay claimed that her weekly essays for the New York Times "offer a model for how to move through our world with insight and sensitivity" and called Graceland, At Last: Notes on Hope and Heartbreak from the American South "a stellar collection that spans nature writing and cultural criticism, the present and the past." I'd read earlier PEN winners and finalists like Annie Dillard, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Ann Patchett and saw a review comparing Renkl's "graceful sentences" to those of E. B. White. Renkl seemed like an essayist I should read.

Graceland, At Last gathers sixty essays from her op-ed column, arranged in separate sections (as she explains in her introduction) "on the flora, fauna, politics, and culture of the American South [. . .] but also on the imperiled environmental context in which the flora and fauna are trying to survive, the social justice issues raised by the politics of this region, and the rich artistic life of a widely varied culture." Each essay has a publication date, none in strictly chronological order. Though some are more narrative and personal and others more editorial and argumentative, all are thoughtful and interesting.

One essay that stayed with me—I dogeared a lot of pages—was "Hawk, Lizard, Mole, Human," the first essay in the opening section, "Flora & Fauna." It is divided into four short, titled parts, each focused on one of those beings. Below the title she writes in italics: "Because William Blake was right: 'Every thing that lives is holy'" and that theme is reinforced in her witnessing of the first three creatures and her reflections on their lives in the fourth section. It's the only segmented essay in the book; the rest are in familiar essay format. I took my time reading through the book, four or five essays a night, and found her to be good company, honest and thoughtful no matter her subject.

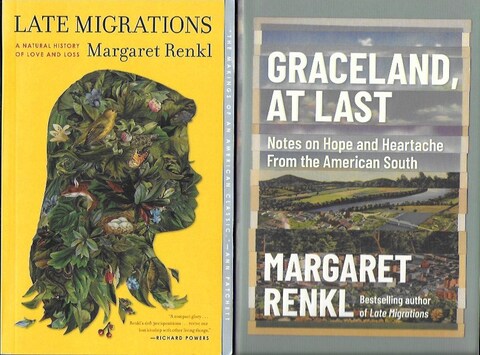

The book contains two pages of blurbs about her previous essay collection, Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss, and the nature of them made it seem even more necessary for me to read it. Ann Patchett compared it to Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and Agee's A Death in the Family as potentially "an American classic." People claimed it "has echoes of Annie Dillard's The Writing Life," the Times called it: "Equal parts Annie Dillard and Anne Lamont with a healthy sprinkle of Tennessee dry rub thrown in," and novelist Richard Powers called it "A compact glory, crosscutting between consummate family memoir and keenly observed backyard natural history." Blurbs are intended to encourage you to read the book. Her first book arrived in the mail before I finished her second book.

Most pieces in Late Migrations are dated, the collection moving chronologically from an account of Margaret's mother's birth in 1931—one of the occasional excerpts edited from transcripts of her brother Billy's interviews with their grandmother, each titled "In Which My Grandmother Tells . . ."—up through "Separation Anxiety," Margaret's account of preparing to drive her sons to their college dorms in 2018. Billy Renkl's artwork sometimes sections off his sister's essays. Some undated essays are taken from her New York Times column, but the dated essays always refer to moments in Renkl's personal history, births and deaths and family events. Much of the material is short, essentially "micro-nonfiction," only a few paragraphs or a single page or two long, expressing and inhabiting flashes of memory and observing the nature around her.

In "Prairie Lights: Eastern Colorado, 1980" she's traveled from her home in Alabama to her boyfriend's family reunion in the west and witnesses a meteor shower: "And, oh, the stars were like the stars in a fairy tale, a profligate pouring of stars that reached across the sky from the edge of the world to the edge of the world to the edge of the world. Even before the first meteor winked at the corner of my eye, I tilted my head back and felt the whole world spinning." The reader is continually, fully invited into the moment the writer relives.

In "Still" she tells us, "Every day the world is teaching me what I need to know to be in the world." Throughout the book her reflections on family and personal history intersect with her reflections on nature and place. In "After the Fall" she realizes, "There is nothing to fear. There is nothing at all to fear. Walk out in the springtime, and look: the birds welcome you with a chorus. The flowers turn their faces to your face. The last of last year's leaves, still damp in the shadows, smell ripe and faintly of fall."

Notes:

Renkl, Margaret, with art by Billy Renkl. Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2019.

Renkl, Margaret. Graceland, At Last: Notes on Hope and Heartbreak from the American South. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2021.